If you’re a food brand large or small, you’re undeniably suited to tap into the power of storytellng as a marketing tool. It’s something I’ve been covering extensively here on my blog.

First, you need to identify your food brand’s story: what is it about your brand, its origins, its commitment and passion is unique. Next, figure out ways to capture and tell your story.

There’s lots more to cover on storytelling to market brands in the food space, but now I want to detour a bit to focus on a different kind of content: recipes.

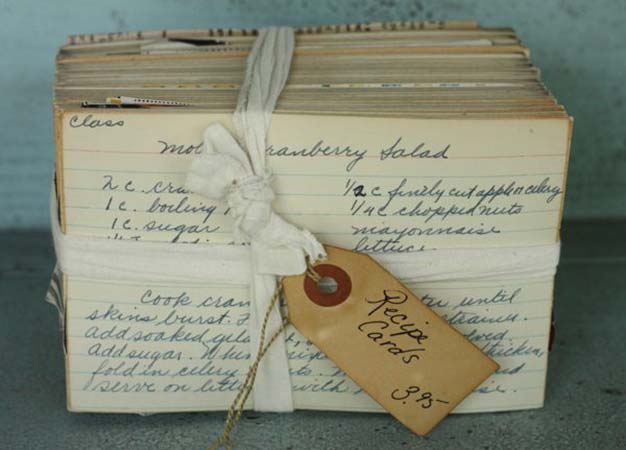

Recipes are terrific marketing content for food brands: Relatively inexpensive to create and photograph, purpose-built to get consumers to your site, eminently shareable on social media.

I do a fair amount of recipe development (research, writing and testing) for retailers and food brands, and I’ve written a cookbook. And as I scan the internet looking at recipe libraries on brand websites, I’m struck by the inconsistent quality of the recipes. They’re poorly written, the instructions don’t make sense, they don’t follow standard formatting. They don’t look like they work.

Here’s the thing: If you take the initiative to share recipes on your brand’s website — and you should — they’d better work. A home cook who discovers that the baking time specified in your recipe is far too long and she winds up burning dinner will be annoyed at the very least. And she won’t come back to your site for more. She may even vent about her burned dinner on social. Ouch.

It’s better to have a curated collection of a dozen recipes that are delicious — and accurate — than to have 30 crappy ones that don’t work.

Here are the most common mistakes in recipes that I see on food brand websites:

Missing ingredients. I see this all the time: recipe instructions that call for adding the lemon zest to the mixing bowl, for example, but there’s no lemon zest in the ingredients list.

Screwy instructions. Steps that are out of order or missing. Unspecified cooking times. Inaccurate temperatures. Omission of key things like softening butter or bringing ingredients to room temperature.

User-provided. Yes, it’s great to invite your customers to share recipes. But someone on your team needs to at least review them for viability, if not test them for accuracy, before you publish them.

Weird measurements. Who can measure out 2/5 of an ounce? Why call for 3 teaspoons instead of 1 tablespoon? How many home cooks have a kitchen scale to weigh grams of sugar?

Written for foodservice. If your produce has foodservice application, you should absolutely develop recipes to help chefs use it in commercial settings. But do not conflate the foodservice and home audiences. Home cooks don’t understand pro chefs’ language (they don’t know the terms Robot Coupe or mise en place, for example). Culinary pros can work with home recipes, but the opposite is not true.

Wrong scale. Related to the above, don’t publish recipes that yield 12 or 24 servings and expect the home cook to do the math to feed 2 of 4.

Incorrect formatting. There’s a generally accepted way to write recipes, for good reason: Home cooks have come to recognize and expect this standard format. If you’re using an in-house creative team to develop recipes, get a style guide. I use “The Recipe Writer’s Handbook.” Better yet, hire a pro to research, write and test your recipes.

To see a brand that does recipes exceptionally well, visit KingArthurFlour.com. This food and bakeware brand puts recipes front and center. They’re vetted in King Arthur’s test kitchen. And talk about building community: They don’t just sell gourmet ingredients and flours; they’ve turned baking into a lifestyle. Nobody does it better.

Take the time now to scan the recipes on your brand’s website. Do they work? Do they look like they do? Do you know? Let me know if I can assist.